Tomer Burg

The best opportunity to view a total Solar eclipse in the United States for the next two decades is nearly at hand. Aside from making sure you’re in the path of totality, the biggest question for most eclipse viewers has been, will it be cloudy?

This has posed a challenge to the meteorological community. That’s because clouds are notoriously difficult to forecast for a number of reasons. The first is that they are localized features, sometimes on the order of a few miles or km across, which is smaller than the resolution of global models that provide forecasts five, seven, or more days out.

Weather models also struggle with predicting clouds because they can form anywhere from a few thousand feet (2,000 meters) above the ground to 50,000 feet (15,000 meters), and therefore they require good information about conditions in the atmosphere near the surface all the way into the stratosphere. The problem is that the combination of ground-based observations, weather balloons, data from aircraft, and satellites do not provide the kind of comprehensive atmospheric profile needed at locations around the world for completely accurate cloud forecasting.

Finally, there is the issue of partly cloudy skies and the transience of clouds themselves. Most places, most days, have a mixture of sunshine and cloudy skies. So let’s say the forecast looks pretty good for your location. According to forecasters there is only a 30 percent skycover forecast for Monday afternoon. Sounds great! But if a large cloud moves over the Sun during the few minutes of totality, it won’t matter if the day was mostly sunny.

With that in mind, here’s the forecast at three days out, with some strategies for finding the clear skies on Monday.

The forecast

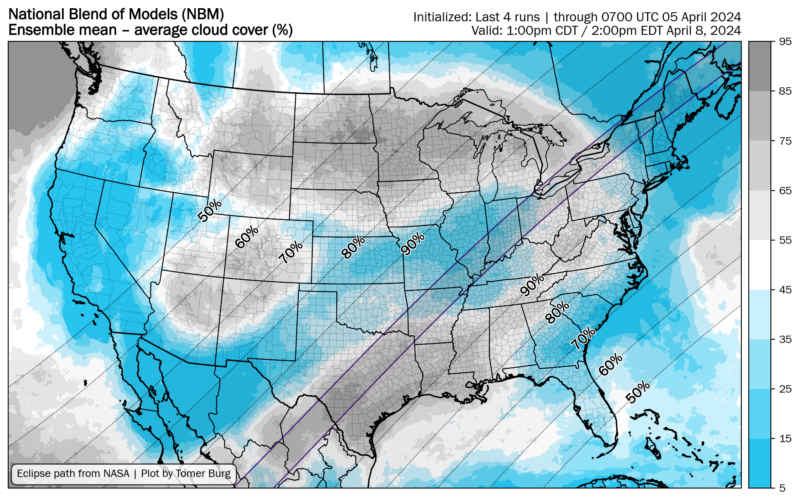

The cloud forecast has actually been remarkably consistent for the last several days, in general terms. Texas has looked rather poor for visibility, the central region of the United States including bits of Missouri, Arkansas, Illinois, and Indiana have looked fairly good, areas along Lake Erie have been iffy, and the northeastern United States has looked optimal.

Our highest confidence area is northern New York, Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine. The reason is that high pressure will be firmly in place for these locations on Monday, virtually guaranteeing mostly sunny skies. If you want to be confident of seeing the eclipse in North America, this is the place to be. But there is a catch—isn’t there always? A snowstorm this week, which may persist into Saturday morning, has made travel difficult. Conditions should improve by Sunday, however.

Rising pressures in the central United States will also make for good viewing conditions. The band of totality running from Northern Arkansas through Indiana is not guaranteed to have clear skies, but the odds are favorable for most locations here.

The Lake Erie region, including Cleveland, is probably the biggest wildcard in the national forecast. The atmospheric setup here is fairly complex, with the region just on the edge of high pressure ridging that will help keep skies clear. I’d be cautiously optimistic.

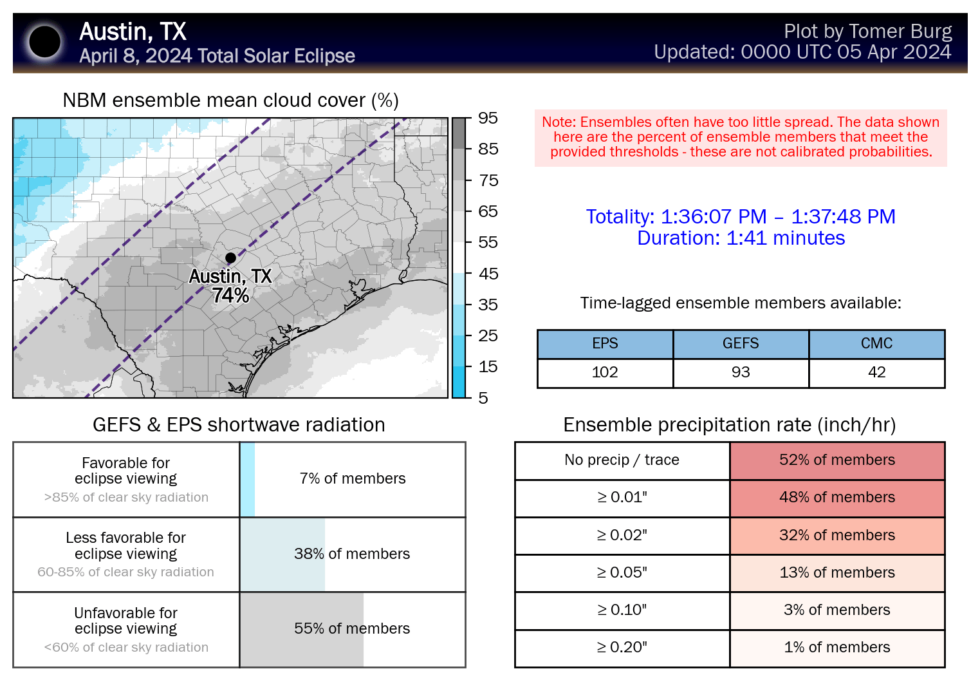

Finally there’s Texas. The forecast overall has been poor since I’ve began tracking it for the last two weeks. (And as I live in Texas, I’ve been following it closely.) The global models with the best predictive value—the European-based ECMWF and US-based GFS—have shown consistently cloudy skies across much of the state on Monday, with a non-zero chance of rain. I do think there will be some breaks in the clouds at the time of the eclipse, perhaps in locations near Dallas or to the west of Austin, and hopefully some of the cloud cover will be thin, high clouds. But whereas the skies at night are big and bright in Texas, the solar eclipse viewing conditions might just bite.

Some strategies for Monday

There are a lot of helpful resources online for tracking cloud cover over the weekend. One of the best hacks is to search the web for the nearest city or town, i.e. “NWS Cleveland, Ohio” and find the “forecaster discussion” section of the National Weather Service website. This will give you a credible local forecaster’s outlook on conditions. Most have been doing a great job of providing eclipse context in twice-daily discussions.

A meteorologist at the University of Oklahoma, Tomer Burg, has set up an excellent website to provide both an overview of the eclipse and a probabilistic outlook for localized conditions. Your best bets are the national blend of models forecast for average cloud cover (direct link), and a city dashboard that provides key information for more than 100 locations about precise eclipse timing and sky cover.

Tomer Burg

Finally, if you’re in the path of totality and are expected to have partly to mostly cloudy skies, don’t despair. There’s always a chance the forecast will change, even a few days out. There’s always a chance for a break in the clouds at the right time. There’s always a chance the clouds will be thin and high, with the disk of the Sun shining through.

And finally, if it is thickly overcast, it will still get eerily dark outside in the middle of the day. It will get noticeably colder. Animals will do nighttime things. So it will be special, but unfortunately not special.