In the 1960s and 1970s, people who lived in rural America fared a little better than their urban counterparts. The rate of deaths from all causes was a tad lower outside of metropolitan areas. In the 1980s, though, things evened out, and in the early 1990s, a gap emerged, with rural areas seeing higher death rates—and the gap has been growing ever since. By 1999, the gap was 6 percent. In 2019, just before the pandemic struck, the gap was over 20 percent.

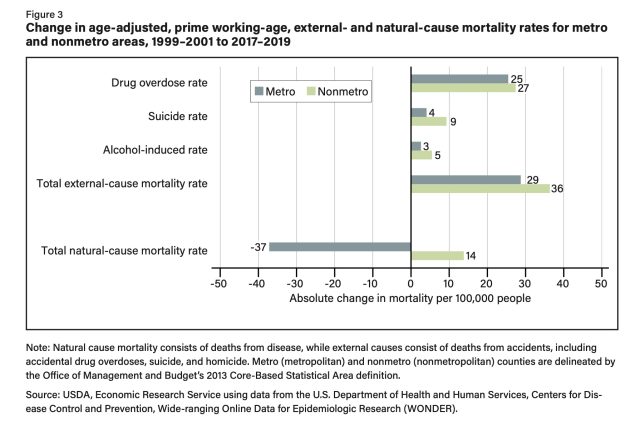

While this news might not be surprising to anyone following mortality trends, a recent analysis by the Department of Agriculture’s Economic Research Service drilled down further, finding a yet more alarming chasm in the urban-rural divide. The report focused in on a key indicator of population health: mortality among prime working-age adults (people ages 25 to 54) and only their natural-cause mortality (NCM) rates—deaths among 100,000 residents from chronic and acute diseases—clearing away external causes of death, including suicides, drug overdoses, violence, and accidents. On this metric, rural areas saw dramatically worsening trends compared with urban populations.

The federal researchers compared NCM rates of prime working-age adults in two three-year periods: 1999 to 2001, and 2017 to 2019. In 1999, the NCM rate in 25- to 54-year-olds in rural areas was 6 percent higher than the NCM rate of this age group in urban areas. In 2019, the gap had grown to a whopping 43 percent. In fact, prime working-age adults in rural areas was the only age group in the US that saw an increased NCM rate in this time period. In urban areas, working-age adults’ NCM rate declined.

Broken down further, the researchers found that non-Hispanic White people in rural areas had the largest NCM rate increases when compared to their urban counterparts. Among just rural residents, American Indian and Alaska Native (AIAN) and non-Hispanic White people registered the largest increases between the two time periods. In both groups, women had the largest increases. Regionally, rural residents in the South had the highest NCM rate, with the rural residents in the Northeast maintaining the lowest rate. But again, across all regions, women saw larger increases than men.

-

Age-adjusted prime working-age natural-cause mortality rates, metro and nonmetro areas, 1999–2019.

-

Change in natural-cause, crude mortality rates by 5-year age cohorts for metro and nonmetro areas, 1999–2001 to 2017–2019.

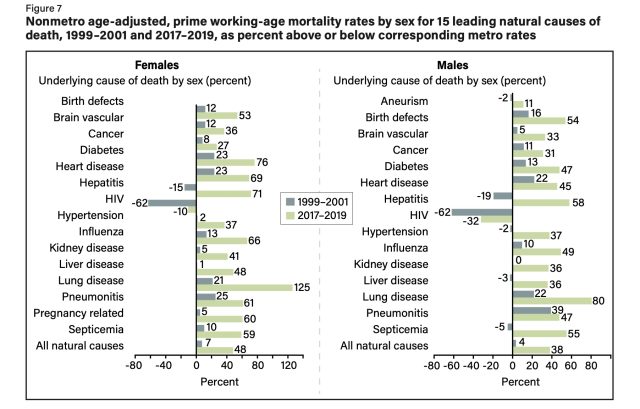

Among all rural working-age residents, the leading natural causes of death were cancer and heart disease—which was true among urban residents as well. But, in rural residents, these conditions had significantly higher mortality rates than what was seen in urban residents. In 2019, women in rural areas had a mortality rate from heart disease that was 69 percent higher than urban counterparts, for example. Otherwise, lung disease- and hepatitis-related mortality saw the largest increases in prevalence in rural residents compared with urban peers. Breaking causes down by gender, rural working-age women saw a 313-percent increase in mortality from pregnancy-related conditions between the study’s two time periods, the largest increase of the mortality causes. For rural working-age men, the largest increase was seen from hypertension-related deaths, with a 132-percent increase between the two time periods.

The study, which drew from CDC death certificate and epidemiological data, did not explore the reasons for the increases. But, there are a number of plausible factors, the authors note. Rural areas have higher rates of poverty, which contributes to poor health outcomes and higher probabilities of death from chronic diseases. Rural areas also have differences in health behaviors compared with urban areas, including higher incidences of smoking and obesity. Further, rural areas have less access to health care and fewer health care resources. Both rural hospital closures and physician shortages in rural areas has been of growing concern among health experts, the researchers note. Last, some of the states with higher rural mortality rates, particularly those in the South, have failed to implement Medicaid expansions under the 2010 Affordable Care Act, which could help improve health care access and, thus, mortality rates among rural residents.